Early this year, Switzerland voted on the topic of a National Basic Income in a referendum. The Swiss voted no, but the Fins are implementing such a scheme starting in 2017. The city of Oakland, CA - where I was just a few weeks ago, is hoping to do so at the end of the year, which would not be a first in the country, since Alaska has had a Basic Income policy for the last quarter century. The Netherlands and France are discussing similar programs. Virtually every OECD country has seen movements created in the last few years calling for this measure to be put in place. Why has this idea - which one can date back to Thomas Paine at the end of the 18th century - all of a sudden become so popular?

For those of you who have not heard much about these debates, a Universal Basic Income (UBI) can be most easily understood as a form of social security system, in which all citizens or residents of a community (most often a country but also regions or cities) regularly receive a set but unconditional sum of money from the government, regardless of any other income the citizen may receive from any other means. Sounds too good to be true? The following will hopefully explain why many today not only think this is possible but necessary.

WHY IS BASIC INCOME POPULAR AGAIN?

Though maybe not the first reason people cite, the real underlying reason for the popularity of UBI seems to me to be necessity. The current social security systems of Western nations are being gradually and structurally pushed to a breaking point and we need to change them.

These social security programs were built on the same logic as insurance. They were designed to help people get back on their feet during brief and rare periods of unemployment. The norm was being employed and paying into the system (mainly through income and corporate taxes). In return, one could call on the system when in need or towards the end of one’s life when retiring, after having paid into the system for several decades.

I will not go into the mathematics of ageing nations, where the number of retiring baby boomers will still increase faster for several years compared to the active population paying for their pensions. This is definitely a piece of the puzzle but not the main problem. The main reason behind the strain of the current social security systems is the gradual and structural erosion and weakening of the middle class and the gradual disappearance of life long employment as the norm.

The erosion of the Middle Class: Being replaced

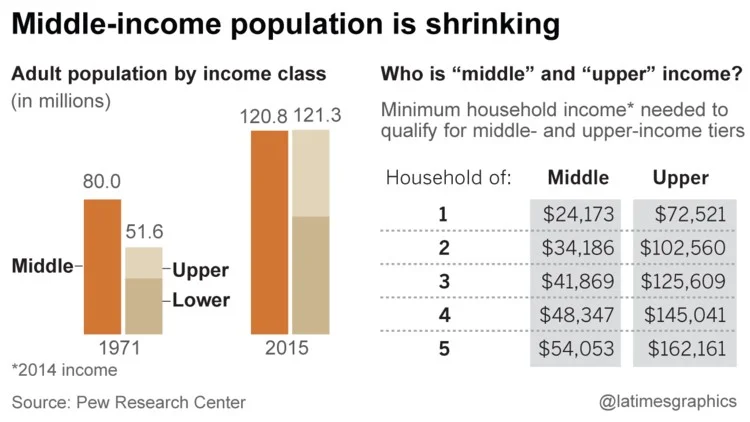

This trend is virtually happening in all nations but none more so than in the United States, where I am writing this piece. As I already mentioned in my post on income inequality, wealth in developed nations is being polarised. The rich are getting richer and the poor poorer. This explains why “Middle America” shrunk by 4% between 2000 and 2014. There are both more lower- and more upper-class members as the following graph shows.

In their fascinating book the Second Machine Age, Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee at MIT, show that the Middle Class is not only shrinking but, along with a growing lower class, are becoming more fragile. Over the last 15 years the median income in America has gradually been falling[1] and the National Bureau of Economic Research has shown that today, 25% of Americans would be incapable of coming up with $2,000 in 30 days and an additional 19% would have to sell major assets (house, car, etc.) or ask family and friends to do so.

According to the two MIT professors, the key reason for this increased fragility is the digitalisation of our economy. I admit that I was at first curious about this argument. Since the creation of the steam engine at the end of the 18th century[2], machines have continuously replaced manual labour and both income and quality of life still grew steadily for over a century and a half. The Industrial Revolution is actually in large part responsible for the creation of the Middle Class. So why would the digitalisation of the economy or the replacement of workers by computers be fundamentally different and detrimental to the Middle Class? The two authors give three main answers[3].

The first very convincing argument given by the two MIT Professors and more concisely synthesised in the following video by the French economist Daniel Cohen (for French speakers), is that the nature of mechanisation and digitalisation is fundamentally different when replacing manual labour for machines. Even though it was not always seen as such but understandably rebellious workers like the Luddites in Britain or the Saboteurs in France, mechanisation of labour during the Industrial Revolution increased the productivity of workers and added value to their work. Because of this added value, wages increased alongside productivity during the whole 19th century and first half of the 20th. The same farmer could plow a much larger field with a tractor than without one and for the same amount of work, produced many more goods, but the farmer was still needed.

In the age of digitalisation, human labour is simply replaced by technology and only in certain cases enhanced (see further down). As Brynjolfsson and McAfee illustrate “An airport ticket agent might find himself replaced by an Internet website he never knew existed, let alone worked with”. In the last decades, median wages have stopped tracking the continuing rise in productivity. This is because Middle Class jobs are the ones being replaced most easily by digital tools.

Daron Acemoglu and David Autor, two other economists from MIT, suggest that work can be divided into a two-by-two matrix[4]: cognitive versus manual and routine versus non-routine. They found that the demand for work has been falling most dramatically for routine tasks, regardless of whether they are cognitive or manual. In other words, digitalisation is detrimental to all jobs that are not highly creative (designers, entrepreneurs, etc.) or in constant interaction with (highly non-routine) humans (like kinder garden teachers, nurses, etc.). These easily replaced jobs are those of the Middle Class: routine administrative work and middle management. Why do you need a tax consultant when you can use TurboTax? Why hire someone to write your weekly financials when computers write them just as well as humans today? Why have a personal assistant when Siri exists?

Setting out for this year of study, I thought I would have to imagine what would happen to us when computers started massively replacing humans at work. Being in the protected bubble of “creative workers”, I did not realise that it was already the case and the answer is that when this happens to you, you usually have to work multiple jobs, with shorter contracts, less security and more frequent periods looking for your next employer. Next time ask your Über driver or helper on TaskRabbit, how many jobs he/she holds[5]?

This leads us to the second structural factor which explains why digitalisation is weakening the Middle Class. If productivity is growing and labour as a whole isn’t capturing the value, who is? The answer, owners of physical capital, to a large extent.

The erosion of the Middle Class: Losing out to Superstars

Evaluating the digital economy is very difficult because a lot of its value does not appear in our classical economic tools. Technically the value generated by Wikipedia is close to zero since no goods or services is being sold. How are you being financially rewarded for organising photos on Instagram or generating the content that other users come to see on Facebook? All the value generated by those millions of hours of “free” voluntary work is held by Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, etc. These concentrate massive amounts of wealth but distribute it to relatively few employees when you compare them to their Industrial equivalents like Ford or Kodak[6]. Digitalisation of the economy multiplies the power, influence and income of the few through Winner-Takes-All markets and Digital Ranking.

A Winner-Takes-All market is a market in which the best performers are able to capture most if not all of the market share, and the remaining competitors are left with very little. If I ask you to name an online marketplace for books, you will no doubt be able to name Amazon.com, maybe another but then most likely you will run out of names. Compare this to if I ask you to name car manufacturers or pharmaceutical companies (itself already a highly concentrated sector). What other search engine do you use besides Google? Digitalisation of the economy encourages such markets because the more the site is used, the more it is useful and attracts users. Why is Facebook so popular? Because everyone is on it. That is why Google+ or MySpace have so few users. In the digital world, there is no second place. If digital companies need very few employees on average and they are in markets which only encourage a handful of companies to exists, it follows logically that they do not generate many jobs and reward highly the ones they have.

Digital ranking is a similar mechanism to Winner-Takes-All markets which creates disproportional returns for a few. When looking for a new camera on Amazon, a place to stay on Airbnb, a restaurant on Yelp, something to watch on YouTube or Netflix, are you not more likely to click on the choice with the highest praise and most positive reviews? With computer doing the first ranking of CVs when hiring for a position using selected keywords, this also means that an employee 90% as good as the top pic will not find a job paying him 90% the top contender’s wages, he might never even find a job. With great ranking, there is not much room for second place either. Brynjolfsson and McAfee call these disproportionate beneficiaries Superstars and they are the big winners of the current digital economy[7]. Unfortunately, average job holders (who hold average jobs, not who are themselves average) which is by definition many Middle Class people lose disproportionately against Superstars.

Moreover, not only the digitalisation of the economy but in general, digital tools favour people at the top. A CEO on his way to work, can email 100’000 employees in a second and get real-time data of all his factories across the globe, thanks to his smartphone but technology has yet to help anyone go through 1000 daily received emails. Digital technology increases many fold the abilities of some at the top of command structures. This in part explains why the ratio of CEO pay to average worker pay increased from 70 in 1990 to 300 in 2005. The digitalisation of the economy may be highly detrimental to Middle Class workers but also continuously strengthens the position of Superstars which is why the both trends are predicted to continue and increase in speed over time.

Additionally, the concentration of means in the hands of few economic actors usually leads to increased economic fragility. The transition from an economy with stable returns to a financialized boom-and-bust economy usually wipes out middle class wealth in the busts but does not rebuild it in the booms. This is what we saw during the 2007 financial crisis.

The erosion of the Middle Class: Having difficulty catching up

The third way digitalisation of the economy is weakening the Middle Class comes from an impossible educational challenge.

As I mentioned previously, the replacement of humans by machines is not all that new and usually required and requires people to train for a new job when their set of skills is no longer useful. With the increasing rate of information and new knowledge being generated, this is an increasingly difficult – some would say impossible – challenge when competing against machines.

IBM has long had a history of creating supercomputers to mimic and beat humans at various tasks[8]: Deeper Blue beat Kasparov at chess and Watson won at Final Jeoperty. IBM is today using Watson to become many things including a diagnostic tool better than any doctor could ever be. Physicians are not in any threat just yet, but they are also falling a bit behind every day. It is estimated that to keep up in his/her field a doctor should read for no less than 160 hours a week of new published medical research. It takes Watson a fraction of a second to integrate that new knowledge to its already huge database of medical knowledge. For now, Watson cannot diagnose as well as a human but once it can, how will a GP catch up. It will be impossible.

Furthermore, Brynjolfsson and McAfee believe that humans hold an advantage over machines in the following fields (for now anyway): Ideation, large-frame pattern recognition and complex forms of communication. They recommend teaching children amongst other skills: self-motivation, curiosity and creativity, to increase this advantage. I am not an educational expert but it strikes me that none of these skills can be achieved in a sort timeframe course. How do you learn to change these deep personal values between two jobs?

To compete against today’s and even more so tomorrow’s machines, humans will have real difficulty keeping up with the pace of change and this means that the time between jobs will not be short and rare moments between long periods of employment but will become the norm. The norm will be constant change and non-linear careers which is exactly what our security systems are not designed to handle.

It is yet unclear if the digitalisation of the economy is just another change in our industrial model, or a deeper shift[9] but there seems to be a certain consensus that we will know a time of increased unpredictability in work patterns and job insecurity. Our social security systems are ill-equipped to address this situation and need to change if we want to avoid an unpreceded wave of pauperisation. UBI is more suited for this new environment as it guarantees a minimum level of wealth for all. However, there are other reason that explain why Basic Income is now such a buzz expression.

Increase social justice

As I mentioned previously, our current economic models struggle to take into account all the value generated by the digital economy and compensate for the work that goes into what some are starting to refer to as Digital Commons. However, and maybe more morally important, on top of addressing those issues, a UBI would acknowledge and provide financial support for the mass of unpaid work - disproportionately undertaken by women - in childrearing, care for the elderly and voluntary help in the wider community, all of which maintains community relationships and support networks. A UBI would address these forgotten issues and massively increase social justice.

Basic income would also increase individual autonomy, enabling people, for example, to escape more easily abusive relationships. It would also most likely reduce crime in general because of diminished poverty.

Furthermore, it is estimated that many people entitled to government aid do not take advantage of it either because of administrative complexity, lack of information or social stigma. As an example, almost a third of people in Britain do not claim the state payments they are entitled to, amounting to around £10 billion of unclaimed aid a year[10]. These are people who society agreed required help but because of the system are not getting it. A UBI, as a much simpler and universal system would solve this issue and most probably reduce State’s administrative cost and also reduce benefit fraud.

On top of helping with all these various issues, a UBI would by doing so, create more social justice and community cohesion which, as I wrote about in my post on Income Inequality, benefits in turn a wide range of societal issues.

Universal income seems universally loved

Surprisingly, Basic Income schemes have been put forward by both right- and left-wing parties. UBI is one of these rare policy creatures supported by both sides of the aisle. For the right, Basic Income is seen as a way to reduce State action and fostering freedom of choice about how to spend that aid. For the left, it is a way to tackle poverty and reinforce equal citizenship and equalise the spread of income.

Though there are foreseeably strong differences between both sides on the way to finance a UBI and what actual social security services it should replace (if any), it is important to note that at first glance, Basic Income is highly bipartisan.

Have we just gotten to that stage?

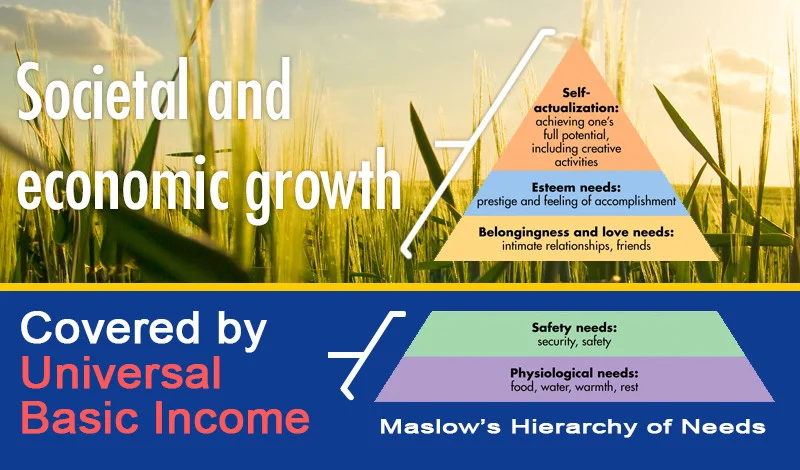

This may be just my way of looking at things since it plays straight into my study’s premise, but I believe that our developed nations have reached a level of development such that we take day-to-day survival as somewhat of an acquired and inalienable right, and that today, we should be more concerned with more advanced ways to further our humanity (purpose, transcendence, etc.)[11]. Besides making sense for many other reasons listed previously, a Universal Basic Income addresses this perfectly. Without the fear of hunger or homelessness, people can choose more freely between leisure and work, find more purpose in their life and have more time to dedicate themselves to others. Some even predict environmental benefits. Since people are considered to more likely find fulfilment in other ways than though material wealth and consumption, physical production should decline slightly[12].

As we have seen, there are many reasons justifying the renewed interest in Universal Basic Income but, there of course also exist some concerns about implementing such a different scheme to what we have known for most of human history. We are after all talking about being paid for doing nothing, to eat the fruits of the garden without painful toil.

THE CONCERNS

I was surprised that I could not find any real counter-arguments to Universal Basic Income. If you have any, please do not hesitate to voice them in the comment section, it would be very helpful. It seems to me, people usually have concerns and seem uncomfortable about such a radically different idea of wealth distribution but their reasoning is more often based on an opinion, doxa, than on empirical evidence. There are four main concerns I have come across and I will try to exlain them below.

People are selfish and lazy

The phrase may seem harsh but the most common criticism of UBI can be boiled down to it. There is this common fear that without the need to work, people will just lazily do nothing all day, taking advantage of the system which will soon collapse because of such an uneven give and take relationship. The most extreme view of this argument mixes in a good dose of generational guilt since it argues that this would squander the wealth prior generations have worked hard to gather for us, their selfish and ungrateful offspring.

This concern is one we all naturally feel I think. We have all felt guilty at one point in time of doing nothing or at least nothing productive. We are scared that we ourselves will take advantage of a system where we could get paid to do this. But how much of that is cultural conditioning in a world where generation after generation had to fight to survive?

I cannot guaranty that this will not happen. However, I seriously question this concern, even having myself on many occasions, spent idle hours watching the most vacuous videos on YouTube. Bertrand Russel in his amazing essay In Praise of Idleness, reminds us that throughout most of history, there has been a class of society virtually paid to do nothing: nobility. Although, we all know that some of its members – maybe even many - contributed very little to society, we have to recognise that nearly all art, philosophy, science and policy, in short human civilisation, up to the 19th century was their doing. Not bad for such a lazy and selfish bunch!

Humanity is driven by more than need, there is desire; desire to learn, to grow, to love, to connect with others. Data actually shows that the countries that consume the most passive distractions (like watching long hours of television) are the ones with the longest work hours. If you come home less tired, you have more energy to take part in more constructive pastimes and spend more time with loved ones, and people in general do just that.

Basic Income, as the name indicates, only tries to address basic needs. In no way, will it take away work. It is actually the opposite. As seen previously, in part it is because work is disappearing that UBI is needed. It is true that we may want to rethink our social values so that we revaluate what to do with this new wealth, to see it as a wealth of time and not just as a wealth to buy things, but I thing society is well on its way to do so.

Companies are selfish

Francine Mestrum, Administrator of the Tricontinental Centre, argues that a Universal Basic Income could shift labour costs that are currently shouldered by corporations to society as a whole. A basic income could therefore become an indirect subsidy to employers who would no longer feel pressured to pay decent wages or provide adequate benefits to their employees[13].

Though this a true concern, it seems to me that it is already happening without Basic Income in many countries and again, I will take an example from here in America. In recent years, corporations in America have increasingly been putting the weight of healthcare on employees, through high out of pocket costs and deductibles. This means that Americans use less preventive care which increases emergency costs and a lot of other related societal costs (including a very low life expectancy for such a country) shouldered by society as a whole.

Moreover, some argue that a UBI would on the opposite, give the poorest employees the upper hand on their employer by strengthening their bargaining position, not needing any job to survive.

How do you pay for a Basic Income?

This just concern relates to the UBI’s financing method. Even among developed nations, individual national economies are too different for there to be a one scheme-fits-all. A country needs to decide on the level of the UBI and which governmental aid programs it will replace. One would need to study each country individually and for most OECDs you can find detailed proposals online.

Usually, depending on personal ideology, one finds different schemes to pay for UBI. More conservative economist, like Milton Friedman, usually prefer to finance it through a flat tax, like a Negative Income Tax. To explain the Negative Income Tax, I will actually let Milton Friedman do it for me, since he gave a much clearer explanation that I ever could in a 1968 television interview.

“Under present law, a family of four (husband, wife and two dependents) is entitled to personal exemptions and minimum deductions totalising $3,000 ($2,400 personal exemptions, $600 deductions).

If such a family has an income of $3,000, its exemptions and deductions just offset its income. It has a zero taxable income and pays no tax.

If it has an income of $4,000, it has a positive taxable income of $1,000. Under current law, it is required to pay a tax of 15.4 per cent, or $154. Hence it ends up with an income after tax of $3,846.

If it has an income of $2,000, it has a negative taxable income of $1,000 ($2,000 minus exemptions and deductions of $3,000 equals -$1,000). This negative taxable income is currently disregarded. Under a negative income tax, the family would be entitled to receive a fraction of this sum. If the negative tax rate were 50 per cent, it would be entitled to receive $500, leaving it with an income after tax of $2,500.

If such a family had no private income, it would have a negative taxable income of —$3,000, which would entitle it to receive $1,500. This is the minimum income guaranteed by this plan for a family of four.”

In this example, there is a Basic Income of $1,500, though one would have to adjust for nearly 50 years of inflation and as I mentioned adapt to each specific country.

In the more socialist schemes, some advocate for social ownership of production means and/or natural resources. Today both those ideas are usually rethought as tax schemes either on capital[14] or on Global Commons (natural resources that belong to no one and so to everyone in a way). Alanna Hartzok, from the Earth Rights Insitute, give the example of a “Global Resource Agency” which could collect resource rents from the exploitation of shared resources such as ocean fisheries, the sea bed, the electromagnetic spectrum, and even outer space[15].

Though it may at first be easier to use an income tax, or even implement a Negative Income Tax to administer a UBI, if we truly start entering a post-work society because of automation and A.I., then other sources of taxation will make more sense.

The challenge of post-work

Though I will write another article at some stage on the possibility of post-work society, Universal Basic Income, or more precisely the reasons behind its recent popularity, bring into question work as our mechanism for resource allocation. Without being a perfect system, work is how we have decided on who gets what for the last centuries.

This last concern is at this stage, fiction and supposition and at this point so hypothetic that it does not constitute for me, a counter argument to UBI. It is much easier to see which jobs technology replaces, much more difficult to imagine what new opportunities (if any) it will create. I will cover this in more detail in a future article, but I felt it an important point to mention here. Following this supposition, there are two prevalent solutions on how to solve this issue: either create democratic institutions to decide on resource allocation or a centralised system. The arguments for both and the implications are fascinating but I will delve into them later. For now, I just wanted to mention this point.

These four concerns constitute the main objections to a UBI. However, the implementation of a basic income could also have interesting implications on globalisation. This is the last aspect I wish to mention.

GLOBALISATION

Though I have mainly written about the developed world in this whole article, I need to mention that Universal Basic Income constitutes a possibility for developing nations also.

Automation and the digitalisation of the economy are also affecting the developing world. Foxconn in China have massively reduced their number of employees by automating their factories and automated help lines are putting many call centre employees in India out of work. If work is no longer a way for developing countries to move out of poverty[16], then taxing Global Commons would maybe make sense and the idea of a “Global Resource Agency” may not seem altogether so much like fiction. As discussed with Guillaume Saint Jacques at MIT, economic borders seem to be losing their pertinence in the digital age and I would argue the same of thinking of the rich and the poor. Maybe we need to start thinking of ourselves as one global communities with different areas where the ratio of rich and poor is different but the issues facing them are to some extent similar: rising superstars and lack of work.

I am going to finish on a very idealistic note but as I mentioned in my post on income inequality, if we gain a more global consciousness, maybe we will be able to finally tackle the issue of global poverty and inequality and not only have developed nation attained a sufficient level of development to eradicate survival needs but one can hope the world has too.

[1] US Real Median Income. Furthermore, the true impact of this has been masked by cheap imports from China and other developing nations which in part compensated on basic goods

[2] And even before but at a much slower pace if you consider such inventions as the printing press.

[3] You can also find here, an interview I conducted of Guillaume Saint Jacques a doctoral student in the same research team as Brynjolfsson and McAfee at MIT, we discuss this point in more depth.

[4] Skills tasks and technologies, 2011

[5] And if he is paying into a retirement plan or healthcare coverage using such services.

[6] My former employer EDF - an industrial age power utility - and Google have roughly comparable yearly revenue of around $70Bn. EDF employs 154’000 employees, Google 59’000 (Q4 5015).

[7] Though it may appear like it, I am not criticising any of this, I am just describing the mechanics at play in our current economy which are systemically forcing our social security system to break and us to change it. There are many positives that come from these new mechanics and I just do not have the time to write about them here.

[8] No wonder Stanley Kubrick called his famous computer in 2001 : A Space Odyssey, HAL in honour of the three-lettered company (HAL is IBM with every letter moved back one in the alphabet).

[9] One interesting way to look at this transition as explained to me by Guillaume Saint Jacques, an MIT doctoral student, is to look at Power systems vs Control systems: “The important changes in previous industrial transition came from the Power Systems: coal to oil to electricity. Today, we are not changing the Power System but the Control System behind the machines. We are not changing where the energy comes from but how we use that energy. “

[10] Dan Finn and Jo Goodship, Take-up of benefits and poverty: an evidence and policy review, Inclusion / Joseph Rowntree Foundation, July 2014.

[11] I have started explaining this theory in more detail in another article.

[12] Which in turn may reduce work even more.

[13] http://www.globalsocialjustice.eu/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=491:the-unconditional-basic-income-a-solution&catid=10:research&Itemid=13

[14] I had this very debate with Guillaume Saint Jacques in my interview with him.

[15] Alanna Hartzog, The Earth Belongs to Everyone, The Institute for Economic Democracy, 2008. See chapter 9 p. 127, chapter 14 p. 172, and chapter 30 p. 334.

[16] An selling natural resources has never seemed to be enough.